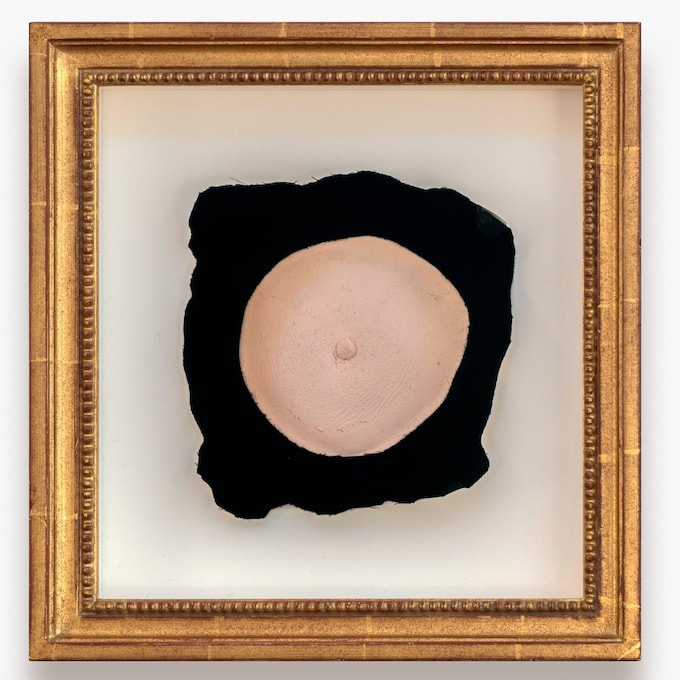

Chest by Anna Weyant

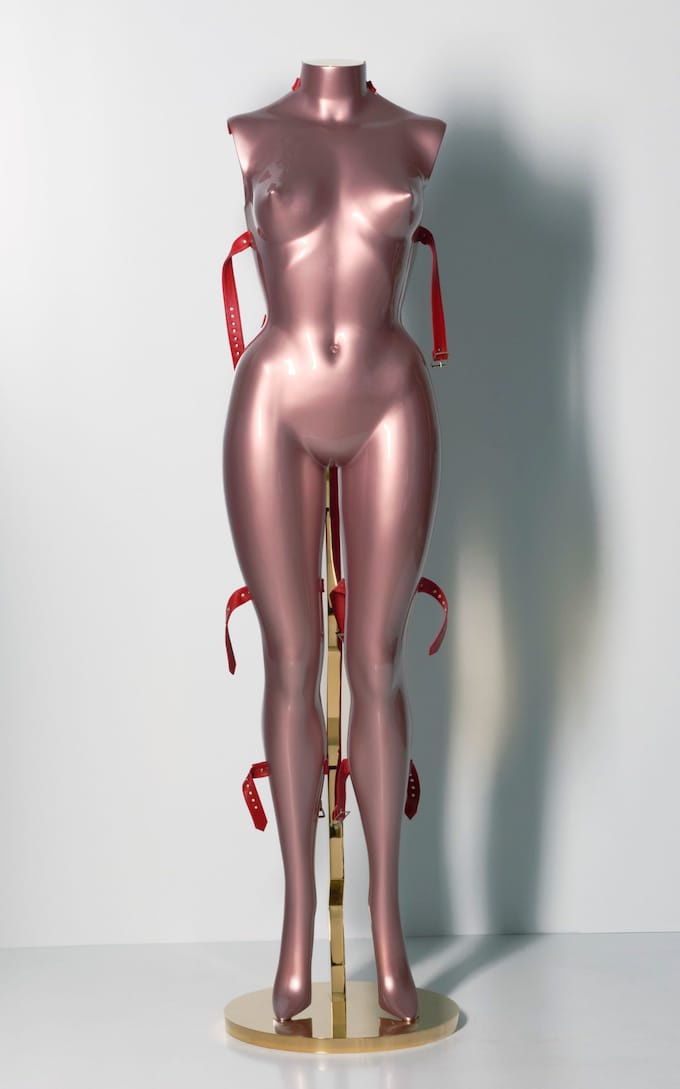

Anyone crossing Venice's Ponte dell’Accademia at night this summer might just make out an illuminated, life-size – and very naked – female form in the window of a nearby palazzo. What stands out most is a remarkably perky pair of breasts.

“Cover Story” (2021) is a brass body-cast headless sculpture by the British pop artist Allen Jones. The work has been positioned in the window by the Italian-American curator Carolina Pasti to lure visitors into Breasts, her group exhibition exploring the mammary glands in art, which has just opened at the Palazzo Franchetti San Marco.

Anyone drawn to the palazzo galleries by the nubile form in the window will find breasts galore of every type imaginable on display – black, white, voluptuous, dainty, bejewelled, damaged by disease and repaired by scarring – in works of different media by 36 artists spanning nearly 800 years.

Pasti has gathered work by artists from a 16th-century Renaissance master to Marcel Duchamp to Cindy Sherman and beyond. The evolution Pasti presents suggests bare breasts fascinate them today as much as they did 500 years ago. What seems to have changed – and very quickly – is the status and power of women as artists.

In this show, Renaissance-era breasts painted by men belong to docile and passive-looking Madonnas. By the 1940s, the surrealist Duchamp had presented Prière de Toucher (Please Touch), a disembodied breast like a framed pudding. Its owner was so passive she was invisible.

But by the 1980s, Sherman had turned the tables. Pasti includes Untitled #205, Sherman’s self-portrait as a parody Madonna in a large gilt frame, wearing absurd prosthetic breasts and a defiant gaze. Sherman leaves no doubt about who controls her nude image.

Duchamp's Prière de Toucher (Please Touch)

And yet this is not a straightforward case of women reclaiming the female breast. It remains a complicated issue – and in many ways, it is still taboo.

The bare male torso is culturally acceptable in public places while the bare female torso is mostly not, despite the best efforts of fashion designers to persuade us to bear the nipple. Yet it is legal for women to be topless in the UK and much of the west (though it remains illegal in three US states: Indiana, Utah and Tennessee, according to the campaign group Gotopless.org, and in several others the law is ambiguous).

When Pasti attempted to promote the photographic works in the exhibition on social media, she fell foul of algorithm censors which flagged them as adult content, though paintings and drawings of breasts seemed to be fine.

Cover Story (2021), a brass body-cast headless sculpture by the British pop artist Allen Jones

Last year, the advisory board to Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, advised the company to reconsider a no-nipples policy for photographs of women (but not men) after years of complaints about censorship of photographs of breastfeeding women, and a high profile campaign known as #freethenipple, which started in the US in 2012 and garnered support from Miley Cyrus and Naomi Campbell, among others.

Today Meta’s “Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity” guidance says it allows female nipples in some contexts such as protests, breastfeeding and scarring after mastectomy and sex-reassignment surgery, for example.

But critics argue Meta’s position still regards women’s breasts as inherently sexual. Given the company’s reach, you could argue we are more unnerved about and censorial of female breasts and nipples than any other time in history.

Sydney Sweeney is likely to agree. The Euphoria actress and Gen-Z favourite found her breasts at the centre of a culture war in recent weeks when she appeared as a guest presenter on Saturday Night Live wearing a low-cut dress. Richard Hanania, a right-wing commentator, wrote on X: “Wokeness is dead”, leading to an inevitable furore. The consensus was he boobed, having misread the moment spectacularly. Sweeney’s critical success gives her the confidence to joke about her sex appeal.

Sweeney’s defiance, however, is not exactly the norm in an age where insecurity still reigns, and many women are still prepared to pay for breast enhancement surgery.

Nora Nugent, vice president of the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (which goes by the delightful acronym BAAPS), says demand for breast augmentation surgery has remained roughly constant over the past decade, with blips over the pandemic. More than 6,500 augmentation operations were carried out in 2022, according to Statista.

Prune Nourry, Oeil Nourricier #6, glass and bronze, 2021

But women are less keen on their new breasts being enhanced purely for the pleasure of others. The enormous, hypersexualised implants of Noughties glamour models have fallen dramatically out of fashion, says Nugent. “There is definitely a downward trend in terms of size. The days of the huge implant are behind us. Women want a more proportional size now.”

Back in Venice, wandering around an art gallery full of images of nothing but bare mammary glands is a strangely soothing experience. Visitors leave a very formal palazzo and enter the galleries through a long, Lynchian corridor draped with blood-red velvet, its ceiling punctured by cartoonish breast-shaped ceiling lights.

There is a cabinet of sculptural breasts, including Duchamp’s lone breast in a frame. Nearby hangs an unsettling 1967 sketch by Salvador Dali in coloured pencils, a faceless woman whose nipples have morphed into gastropods. “Nude with Snail Breasts” is one of the more alarming works in the show. Even when artists are confused about breasts, they are repeatedly drawn to them. But what makes the Venice exhibition special is that all those breasts together become less erotic and more magnificent, funny, intriguing and humbling.

Bernardino Del Signoraccio's 16th-century 'Madonna of Humility'

The British artist Charlotte Colbert’s Mastectomy Mammeria of 2019, a tower of powder-white dismembered breasts, sits as a centrepiece to the Venice exhibition like a lovely meringue. Colbert believes taboos are linked to a lingering squeamishness about breastfeeding and ultimately a fear of intimacy. “It feels bonkers,” says Colbert. “You would think we would all be more humble about our relationships to women’s bodies because they are awesome things.”

Returning to Del Signoraccio’s 16th-century Madonna of Humility, I see her point. The humility could be the resigned Madonna surrendering to the demands of the Christ child. Or it could be our humility in the face of her body’s ability to sustain life. Her natural munificence.

Perhaps this exhibition’s greatest achievement is the proof it offers that artists have always objectified and politicised breasts. The only difference is the era. Del Signoraccio’s Madonna was intended as an example to mortal women. Half a millennia later, Colbert’s tower of everyday mammaries feels like a plea for autonomy in a confusing era of proud nipple liberation on one hand and unseen censorial forces on the other. And Jones’s seductive woman luring us from the window turns out to be a hollow cast. She makes suckers of us all.